Dr. Gail Levin

Distinguished Professor, Baruch College and the Graduate Center, CUNY

The name Theresa Bernstein already meant something to me when I read that she was in a show, “Paintings and Prints by William Meyerowitz and Theresa Bernstein,” at The New York Historical Society (October 5, 1983- April, 29, 1984). I had first read about her in Walter Tittle’s diary as one of the artists who had worked with Tittle, Edward Hopper, John Sloan, Randall Davey, and others to hang a group show at the MacDowell Club in April 1918.

Surprised to find that Bernstein was still living, I decided to look her up after seeing the show. I liked her painting and during the many years that I had been researching Hopper, it was rare enough to meet artists who were his contemporaries. Still working on Hopper’s catalogue raisonné, I was eager to meet Bernstein. She had stories to tell about both Hopper and his wife, Jo. The two couples knew each other both in the city and in Gloucester, where the Hoppers had painted in summers during the 1920s, before switching to Cape Cod in 1930.

Bernstein herself made a strong enough impression on me that when I was asked to write an essay for the catalogue of the inaugural show at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (which opened in April 1987), I insisted on discussing her in my essay, “The Changing Status of American Women Artists, 1900-1930.” I managed to illustrate my essay with a reproduction of her painting, Waiting Room Employment Office (1917), even though I was unable to convince the curator to add to the show an artist whose work she did not yet know.

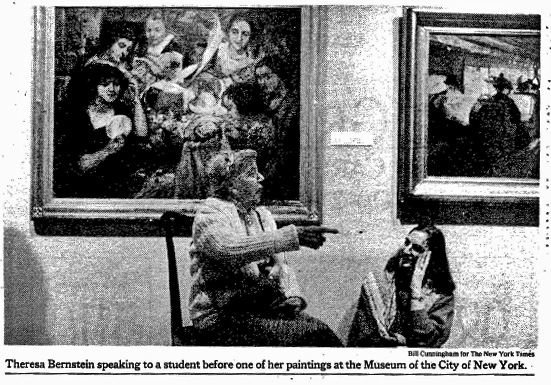

A little over three years later, “Echoes of New York: The Paintings of Theresa Bernstein,” curated by Michele Cohen, opened at the Museum of the City of New York (November 20, 1990 to March 31, 1991). I saw the show as an opportunity to have my art history seminar from the CUNY Graduate Center meet Bernstein and discuss her work. I arranged for an interview to take place in her show on February 16, 1991. The museum summoned The New York Times, which sent a reporter and photographer Bill Cunningham to record the group visit. The next day the story described Bernstein as “100 years old (or 101 or 102—she never will really say)” and quoted her, “I never got frustrated, because I didn’t expect anything. I enjoyed painting the works I did. I didn’t do it for public acclaim.” Bernstein “spent several hours at the Museum of the City of New York talking about her work to graduate students from the City University of New York,” said the Times. She was effervescent, obviously enjoying the attention. Cunningham took many pictures, printing one of me seated on the floor at Bernstein’s feet with the caption, “Bernstein speaking to a student before one of her paintings at the Museum.”

By then I was working on a biography of Edward Hopper and wanted to meet Bernstein in Gloucester, hoping to evoke more memories of the Hoppers. So the following summer, I arranged for my husband and I to call upon Bernstein at her home there. I enjoyed seeing her in the house that she and William had lived in since 1924, the very year that the Hoppers honeymooned in Gloucester. She recalled holding “soirées” at the house attended by Edward and Jo. I remember Bernstein’s affection for her nephew Keith Carlson, who was living in Gloucester that summer.

Bernstein did have a cameo role in my book, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography , first published in 1995. Only while researching this current project, however, did I come to realize that she had counted on my writing about her art. In a June 17, 1991, transcript of an oral history in the New York Public Library, Bernstein told Muriel Meyers of the American Jewish Committee, “Gail Levin, who wrote the book on Edward Hopper….took a great interest in my work. She feels that I haven’t as yet reached the appreciation that I deserve for my career. So she has been interviewing me and she’s working on a book….” Although I did see Bernstein at her solo show in 1998 at Joan Whalen Fine Art on West Fifty-seventh Street in New York, I had no thought that I would ever write a book on her. That happened almost by chance, when the opportunity to teach an exhibition seminar came my way. I wanted to see that Bernstein was finally inscribed into history. I thought that working on Bernstein, who had received so little scholarly attention, would be a great opportunity for graduate students, whom I hoped would work with me on the project goals of organizing an exhibition and writing essays for a book on Bernstein. And so they have: Theresa Bernstein: A Century in Art (University of Nebraska Press, 2013) is in press and the show will open at the James Gallery of the Graduate Center on November 12, 2013, before traveling to four other venues. I now know that Bernstein foresaw the value of this endeavor long before I did.