Girard “Jerry” Jackson

Friend

Knowing Theresa Bernstein and William Meyerowitz was a privilege. The husband and wife artists guided me on an extraordinary journey in the visual arts. Of course when I first came across Meyerowitz’s works, years before I met the gifted painters, I had no idea of the colorful path that would follow.

Maine beckoned a friend and me for canoeing-fishing in the summer of 1966. As we soon discovered, Joan Purcell, a Long Island artist, had rented a barn in Bar Harbor as a gallery to sell art. Joan had included several works by the artist William Meyerowitz. I bought a small painting of a trio of musicians by Meyerowitz and two of his etchings in color—one representing three ballet dancers and the other a violinist. Although I had had no training in art history, I found his musical subjects irresistible.

Very soon I was to come upon Meyerowitz’s work a second time. In 1968 I was in New York on business and happened to see an interesting Meyerowitz painting—a cellist as I recall—at the Chase Art Gallery on East 68th Street. I didn’t forget about it. I moved to Connecticut from Austin, Texas in 1972, and once settled, I returned to East 68th—probably in early 1973—to find that Chase had closed.

At that point, I decided to take more direct action. Meyerowitz was listed in the phone book at 24 West 74th Street, and I dropped him a note to introduce myself. He replied with an invitation to lunch at his and his wife’s studio on 74th. The studio was a large room with many windows facing north. The walls were covered with his paintings, and Bernstein’s large Polish Church painting hung over the piano. There were two easels, a pull-out sofa, a roll-top desk, a book case, a chest and steps leading to the balcony. A dressing room separated bath and small kitchen next to the entry. As we became acquainted, a mouse ran across the floor.

Meyerowitz was a jovial fellow. A hint of his Russian youth lingered in his speech. While both artists were articulate, Bernstein’s mind was a magnet. She could embellish any conversation with her total recall. During conversations after lunch, she made sure different examples of Meyerowitz’s works were rotated on the easel. The petite Bernstein did her best to let Meyerowitz dominate the conversation; she tried to be subdued. As I quickly became aware, however, that wasn’t easy for this natural raconteur. She loved to tell Yiddish jokes, and her laugh was contagious. Still, Meyerowitz held his own. When we were better acquainted, William’s baritone often broke into song. In earlier days he sang in the chorus at the Met and the Presbyterian choir in Gloucester, Massachusetts where the two had a summer home. He was, in every sense, a mensch.

We became friends and visited back and forth—New York, Stamford and Gloucester. I became William’s regular client. I immediately liked his Gloucester scenes and recognized that he was a fine colorist, but it would be years before I appreciated his unique brush work. I realize now that he may have been inspired by Bernstein’s paint-to-canvas techniques. In any case, Bill’s etchings in color are exquisite and unique.

In a letter of August 2, 1976, Bill described his process for etchings in color:

There were a number of people throughout the history of etching who have tried to introduce color in etching; but it was not of any success. Among the impressionists Mary Cassat [sic] and Pissaro introduced color in etching with a little more success than previous artists.

When I started to show my etchings in color many artists were against it including Joseph Pennel, who asked me finally how do [sic] I do them. I told him that, that [sic] this was my secret. At any rate lots of artists do now print in color but all are litographs [sic] and are printed by the litographer [sic] on a litographic [sic] press. Mine are done by hand like a regular etching. The color is applied onto the plate and printed on my etching press. In looking at many exhibitions here and abroad, we did not see any etching in color to have the quality as mine….

Bill was right. This fine printer’s etchings are truly novel. Different colors required multiple pressings—a tedious, demanding job. He also printed Bernstein’s exceptional monotypes on his press, likely with her help.

Another obvious strength of William’s work is the inventiveness of his figures. Dancers, musicians, fishermen and horses remained his favored subjects throughout his career. He had immediate experience of all of these areas, even going so far as to watch rehearsals at the American Ballet Theater.

In the meantime, Bernstein did her best to avoid showing her work. When she did, William wasn’t always pleased. She expressed displeasure at his abrupt rudeness only once in my presence. In the years before William died, the only Bernstein I bought during the first eight years I’d known her was a wonderful Coney Island 1914 watercolor.

Although both artists were still actively painting, their conversations involving artist colleagues were most often in the past tense. They told personal stories involving well known individuals of the art world, referring, for example, to Childe Hassam lying drunk on the stairs at a Whitney Studio Club party at Gertrude Whitney’s. William considered Oscar Bluemner a close friend. Bernstein held John Sloan in high esteem and felt a kindred spirit with Stuart Davis in their shared love of jazz. Davis and his mother had a house on Mt. Pleasant Ave. in Gloucester. He and Bernstein would stay up late listening to jazz on the radio, probably at Bernstein’s Mt. Pleasant home. She was an ardent Louis Armstrong fan. At times William seemed to play second fiddle to his outgoing wife. Often ending a tale from earlier days Bernstein would say “and Bill too.” Downcast, Bill said, “I was always Bill too.”

There was a hint of the equal partnership this couple had formed on one of their visits to Stamford. I thought they’d enjoy a choir program at the church. It was a short walk from our apartment. I walked a short distance ahead of Bernstein and Bill to be in the choir, but I did hear Bernstein growl: “I don’t want to go to that goddamn Presbyterian Church.” She walked with a cane and it was down a hill. This venture for a client of William’s was beyond her limit. Even though they might have enjoyed the church architecture—built in the shape of a whale—Bill probably hadn’t heard the end of Bernstein’s dissatisfaction. He owed her one.

In spite of frictions, their marriage was a daily romance, at least when sales weren’t involved. When William’s art was on the easel, Bernstein acquiesced. She defined their marriage as a constant conversation. It was. Considerable effort and thought must have been invested over the years for two strong-willed artists to achieve their harmony. I’ve seldom witnessed such a lasting love affair.

Theresa and William left for Gloucester soon after our first meeting, as they continued to do every summer I knew them as a couple. Neither drove, so Diane Dawson who grew up next door to them in Gloucester drove them back and forth. As they grew older, Diane saw to their needs during summers. The house in Gloucester at 44 Mt. Pleasant Avenue is a two-story Georgian with a basement at ground level in the back where William had his studio. Bernstein’s studio was on the first floor, facing the street. The kitchen, living room and dining area with a pot-belly stove were separated by an entry hall with stairs going to the second floor bedrooms and bath. A bath was next to the kitchen. Most of the art work on the walls was William’s, but Bernstein’s 1955 Judy Garland oil hung in the dining room. There was a piano and a non-functioning organ in the living room. In winter after the trees lose their leaves, there’s a view of the Atlantic to the east.

By the time I met them, public exhibitions of their work were mostly joint. Bill did the manual labor—packaging and shipping—preparing for shows. I know of one joint exhibition that may have been contentious. Bill confided in me: “If she wasn’t in the show I’d be able to send more of my work.”

After our friendship had lasted nearly a decade, Bill’s life came to an end. His final illness with cancer in 1981 was brief but disabling. Theresa called on a Sunday morning and I took them to a hospital downtown. Theresa appeared fragile. The young doctor was sympathetic and called a week or so later asking me to tell Theresa that William had died. My niece Pam Smith and I went to the funeral. After the service, Theresa came toward us—cane in hand—“I want to see more of you.” As we left, Pam said “She won’t last a month.” I agreed. Seldom has a prediction been so completely off base.

Theresa sat shivah vowing to compile photography of William’s art for a book. It took more than a year but she did just that. Her book, William Meyerowitz: The Artist Speaks, was published in 1986.

Living the Bohemian life with money in the bank, the couple had spent little. The single exception to their frugality was their annual trips to Israel. Theresa wasn’t a spender, but after William’s death, she did begin to acquire necessities that come with age. She hired daily help and had the studio cleaned. Her accountant, Suzanne Laurier, oversaw her care. Suzanne brought in an exceptionally good caregiver—her name was Juanita, but Theresa called her Janeeda. Juanita did her best the keep the studio in good shape.

I once asked Theresa why they didn’t have help when William was alive—especially during his illness. Was William too cheap? Livid: “None of your business.” I asked who would have taken him to the hospital if I hadn’t. She said, “I would.” She probably could have managed. Once she decided she could do something, she did it.

Even after Bill’s death, Theresa continued to acquire friends easily. I met a young woman who’d become a friend and asked how she’d met Theresa. She explained that Theresa had wanted a certain book. In her nightcap she got a cab and crossed town to a bookstore. The new friend said Theresa had bogged down in a pile of snow so she took her—book in hand—back to 74th Street. She’d only known my cousin Mallory Young an hour, when they started reciting the Iliad back and forth from memory as though they’d known each other for years.

About a year after William’s death, the Jewish National Fund held a well attended memorial service for him. With Theresa spiffily dressed thanks to Juanita, we flagged a taxi on 74th Street. She insisted on taking a painting of William’s, one that looked like a Gloucester scene to me. She scooted across the back seat of the cab to make room. The cabbie looked back in astonishment saying “She’s strong.” It then dawned on me: Theresa still had mileage. When asked for words at the service, an animated Theresa in her cocked hat took charge with confidence: “Well, you can’t beat time because time won’t like it.” The crowd was soon roaring with laughter. Touting William’s painting as the “trees of Israel,” she sold it before the end of the service.

Theresa had turned the page. Conversations became future tense or focused on the now. Her greeting was often “What’s next?” Frequently, she answered that question herself. For example, she called the New-York Historical Society and asked, “You wanna see some pictures of New York?” Someone was intrigued, and Elizabeth Curry—a Society curator—visited the studio. I don’t know what Theresa showed Ms. Curry—we called her Betsy—but it was the beginning of the 1983-84 Society exhibition New York Themes: Paintings and Prints by William Meyerowitz and Theresa Bernstein.

Only gradually did I become aware of the number of her own works Theresa had stockpiled away. On one occasion, Theresa asked me to go on the studio balcony and look for certain canvases. The floor was covered with piles of unstretched paintings and maybe three or four stacks of watercolors. It was a eureka experience. There were her paintings Searchlights on the Hudson, In the Elevated, Waiting Room—Employment Office and on and on. When I asked, “Theresa, why didn’t you take care of these canvases?” she retorted, “That’s not my job, it’s somebody else’s.”

There was a large unstretched painting standing against the balcony wall. Its only support holding it upright was the ruffled canvas and the paint. I asked Theresa about the painting and why it wasn’t on a stretcher. “That’s the old Metropolitan Opera” building. Bill took my stretcher.” Her tone told me I’d hit a nerve so that was the end of that.

Once I had seen Searchlights on the Hudson and In the Elevated, I took the canvases over to the Historical Society to show Betsy Curry and her co-workers. They looked at the canvases laid out on the floor. Oh yes, oh yes was their immediate response. Let’s exhibit those.

Although their quality was immediately apparent, the paintings needed restoration and framing. Fortunately, Theresa had used good quality paint so that was mostly intact, but the canvases were dilapidated. Having bought William’s paintings, I’d been introduced to the restorer-conservator Renzo Baldaccini at1100 Madison Ave., probably around 1975. Renzo was a Florentine trained in architecture with years of experience in conservation. He’d married a New Yorker after the war and moved to this country. His assistant was Gloria Signorelli, an art history major who studied conservation summers in Florence.

But first I had to face negotiations with Theresa to buy the works. When I had bought Bill’s art, Bill had negotiated his sales with Theresa often gasping—I never knew why, maybe a part of her act—but up to this point, I’d only bought the Coney Island watercolor from her. Negotiations proved uneventful with Theresa quoting prices not much higher than I’d paid for William’s larger works. I bought Searchlights on the Hudson and In the Elevated and soon became that “somebody else” to take care of canvases. Signorelli had conserved the watercolor several years before. Renzo was enamored with Theresa’s work and there are few canvases I purchased that haven’t known his or Gloria’s expert hands. Gloria works on the Meyerowitzes’ art to this day at 1100 Madison. Although I have heard of problems with some works restored by other restorers, I’ve never had a problem with Gloria or Renzo’s relined canvases or conservation.

The Historical Society exhibition was successful, mentioned by Grace Glueck in her New York Times art review October 13, 1983, and was extended from February to April 24, 1984. Theresa went to the Society often during the show. It’s a short walk from her studio on 74th to the Society on Central Park West between 76th and 77th Streets. She made new friends and found new buyers. Visitors came calling at 24 W. 74th and Theresa was ready.

My discovery of Theresa’s works was not limited to those stored in the New York studio. Shortly after the Society show she asked me to go to the attic in Gloucester. More stacks of paintings. There were the 1919 Grecian Pageant; the 1920 Joy of Life; 1919-22 Music on the Shore; Four Freedoms Parade, Rockport, July 4, 1944 and many others. Surprisingly, the canvases and their paint had weathered better over many years in the hot attic of Gloucester summers than the New York balcony works.

But I was not the only one Theresa allowed—or pressured—to patronize her work. Pam and our friend Jim Fish visited Theresa in Gloucester, probably in the summer of 1984. Jim later recalled the visit. Pam called on her return to New York from Gloucester. “You know what Theresa did? She slammed the door in my face.” Theresa had quoted Jim a price that Pam thought might be too high. She had said “You better check with Jerry, Jim.” The three were standing in a doorway in Gloucester; Theresa did a pirouette, closed the door shutting Pam out and sealed the deal without interference. As it turned out, however, Jim didn’t get a bad deal: William’s painting is one of his best harbor scenes. Jim left the paintings in Stamford; Renzo worked on them and they were shipped to Jim in New Mexico.

I was astonished at the quality of Theresa’s work. Her luscious brush work was something I hadn’t seen since Caravaggio’s. A few of the subjects—especially her figures—remind me of Edvard Munch; see her 1917 Hawthorne Lane. There are echoes of Honoré Daumier. I began buying and conserving paintings. They had to be seen. How could they have been ignored all these years? I didn’t have a clue where I was headed, but the avocation was good divorce therapy. Renzo advised, “You should compile a catalog.” So Pam and I did just that. Pam did black and white photography and the graphics. Theresa and I worked on an essay hours on end in Gloucester. She was a good writer. Pam and I published Smith-Girard’s catalog Theresa Bernstein in 1985. The catalog was mailed to museum and public libraries around the country.

Our efforts to gain recognition were often met with satisfying success. In 1987 Patsy Whitman, Stamford’s artists’ patron, called and asked to see Theresa’s work. She contacted her friend Dorothy Mayhall, Director of Art at the Stamford Museum and a gifted sculptor: “Dottie, you’ve got to know Theresa Bernstein’s art and have a show.” Mayhall met Theresa, they hit it off and Theresa Bernstein, Expressions of Cape Ann & New York, 1914-1972 opened at the Stamford Museum in November 1989, then traveled to Boston to Simmons College and the Crane Collection in January 1990. I’d found a good photographer for color transparencies, and Pam included some color reproductions in the catalog.

Imagine the surprise when I opened the Connecticut section of the Sunday, December 31, l989 New York Times and read a positive review by William Zimmer. Janet Koplos, art critic of the Advocate and Greenwich Times wrote of my catalog essay: “[P]rovides much interesting information, but is too effusive and sentimental to be critically trustworthy. Bernstein doesn’t need to be coddled.” That’s true.

Art Historian Michele Cohen had befriended Theresa during the Historical Society exhibition and had offered to co-author the Stamford Museum catalog essay. Not realizing the importance of formal training in art history to guide a viewer’s eyes through an exhibition with the written word, I mistakenly declined Michele’s offer. The essay would have been more credible had an art historian participated in the writing.

The recognition Theresa had received in her early career was mostly from critics, galleries, publications and buyers, but acceptance of her abilities was impossible for some male peers. The acceptance conversion Theresa was at last earning provided a strong contrast to earlier experiences. In the catalog Mayhall describes Theresa’s early experiences with exhibitions:

Early in her career, Bernstein began to experience—and suffer from—the discrimination of galleries, museums and newspapers toward women artists. As was customary at the time, she often signed only her first initial when exhibiting her work, especially at New York’s National Academy of Design. Many times a Bernstein painting was selected by a jury for an academy exhibition, then without explanation suddenly withdrawn, or not shown at all when her feminine identity was revealed. The strength of her work caused many critics to assume it had been the work of a man.

Theresa related a similar academy experience to me. A jury had selected a painting—possibly the 1914 Readers, I’m not sure—for exhibition. It was exhibited but hung under a stairway railing with a potted plant hiding most of the canvas.

But times had changed. Before the National Museum of Women in the Arts in DC opened in April 1987, Eleanor Tufts, an art history professor at SMU in Dallas and the curator for the opening exhibition, called, unhappy because she had only seen our S-G 1985 catalog after curating works for the show. Dr. Tufts asked for a photograph of Theresa’s Waiting Room—Employment Office painting. Although it was too late to include a Bernstein work in the exhibition, Gail Levin saved the day mentioning Theresa and reproducing her Waiting Room—Employment Office painting in black and white within her catalog essay.

The phone began to ring. Elsa Honig Fine, editor and publisher of the Woman’s Art Journal called in 1987. “I must publish Theresa’s work in my journal.” She called Professor Alicia Faxon at Simmons College to write an essay about Theresa. Dr. Faxon was busy with her Pre-Raphaelite Dante Rossetti catalog, but she mentioned Simmons faculty art history professor Patricia Burnham. Not much later, Dr. Burnham, whom we call Tish, met Theresa and came calling in Stamford to see and photograph Theresa’s art and to borrow photographs for reproduction. It was the beginning of a long Burnham-Bernstein relationship. Dr. Burnham’s essay on Theresa appeared in the Fall 1988 / Winter 1989 issue of Dr. Fine’s journal. Tish and Theresa remained friends, and Tish continued chronicling Theresa and her art. They spoke often of a catalog or monograph of Theresa’s art to be authored by Tish.

Fine told Tish she’d never heard of Theresa but many women artists—Fine named Elsie Driggs and others—had insisted she write about Theresa. When Theresa walked into the gallery at the ACA Gallery 1987 exhibition on Madison Ave., New York Women Artists in 1925, the other women artists—most younger than Theresa—greeted her as though the queen had arrived. (Tish has been told that there were women who joined the organization after 1925.) The artists weren’t the only ones to celebrate Theresa at this event. Until then, Baldaccini hadn’t met Theresa. He came to the gallery that day and, on meeting her, promptly kissed her hands. Theresa flashed him a sly smile and responded, “Oh, so French,” with a shimmy Mae West would envy.

More exhibitions followed. There was Michele Cohen’s successful show at the Museum of the City of New York in 1990-91. The Jewish Museum’s 1991 exhibition Painting a Place in America, Jewish Artists in New York 1900-1945 included fine works of Theresa and William. Their work could be seen at exhibitions on Cape Ann in the summers. Fine art reproductions and/or profiles of Theresa appeared in the Boston Globe, New York Times, The Christian Science Monitor and Cape Ann papers during shows. And naturally publicity and exhibitions brought sales and an increase in prices.

Not all clients got off as easy as Jim Fish. Super salesperson Theresa didn’t like for a visitor to leave without a purchase. She had an extra sense to detect discretionary funds. The adrenalin was especially active with a fellow Semite: “I don’t know where my next meal is coming from. My expenses are more than I can bear. Won’t you help me? It’s a good one. Come on. You can swing it.” If all else failed, she’d lock the door until a sale took place.

Thankfully Theresa had begun recommending buyers to Baldaccini for art that needed cleaning or restoration. That was a relief. She’d been reluctant to recommend Renzo. He was expensive. Finally recognizing Renzo’s expertise, she had even started sending him works.

Throughout the eighties, Theresa was a fixture on Columbus Avenue. We’d walk the block, around the Dakotas and back up Columbus. Faithful to Robert Henri’s challenge—paint what you see—one of her last canvases was the 1983 Smoochathon. There was a lingerie shop on Columbus between 73rd and 74th Streets. Couples held kissing contests in the window for several weeks. Theresa’s gaze memorized the scene. The break dancers also fascinated her—a new subject to express. She continued to work with watercolors, painting every day—“I need to keep my fingers nimble”—and often swearing, “The easel painter is dead.”

As much as I was enjoying spending time with Theresa’s art, my work as a patent lawyer, mostly pharmaceutical and agricultural, was demanding. By the late ‘80’s I needed to slack off this avocation. Theresa’s prices had improved and were getting out of my range. Selling works to meet avocation expenses was also improving. Theresa wasn’t happy when I ended purchases in the early 1990s. “What will become of my beautiful work?” Although I’d become that “somebody else” to see to her art, she mostly thought of me as a collector which I’m not. But she had no real worries. The market was absorbing the work and she was doing well. Her summers were full: she was the reigning doyenne artist on Cape Ann. She relished the attention. And with effort, we remained friends.

After retiring in 1996, I moved back to my native Texas. Theresa and I talked often and I spent time on Cape Ann the following summers. As it turned out, Tish Burnham had also moved to Texas. Her M.I.T. professor husband had been offered a chair in the history department at the University of Texas. Tish had given up her job at Simmons and they had moved to Austin in 1988. Tish joined the faculty at the university and instigated the 1996 exhibition of William’s etchings at the university’s Blanton Museum. Theresa didn’t attend the opening but sent her emissary, Suzanne Laurier.

In 1998 I completed work on a house at 836 Lakeview Dr. in Sugar Land to display the art. I was painting a bathroom when the phone rang: “This is Joan Whalen, Joan Whalen Fine Art in New York. I want to have a Theresa Bernstein exhibition.” Joan had met and visited with Theresa. A week or so after Joan called, she visited my home to see the art, and her exhibition Theresa Bernstein, A Seventy-Year Retrospective opened at her 57th Street gallery February 25, 1998.

I took Theresa to Joan’s opening. The crowd spilled out onto 57th Street. Theresa was interested in people and she usually followed an introduction to a stranger with “What do you do?” A young woman at the show introduced herself and Theresa queried, “What do you do?” “My husband is a physician and I never see him.” “I didn’t ask your state of mind,” came the response, “I asked what you do.” Clearly Theresa had lost none of her sharpness. Joan Whalen had a second successful exhibition of Theresa’s art in 2000. If there is a heaven, there has to be a place for art dealers like Joan and Bonnie Crane in Massachusetts. Such exhibitions are a gamble and frightfully expensive, especially in New York. Joan has a saying, “If you want to have a million dollars selling art, start with five million and quit when there’s a million left.”

When the Sugar Land house was completed it was party time. Theresa planned to come to the open house in October 1998 but was ill and sent a VCR greeting instead. Tish Burnham lectured. Dr. Danuta Batorska, the art history professor for the classes I’d enrolled in at the University of Houston, came. She perused the paintings and pointed at the 1917 Hawthorne Lane. “I like that painting.” She wouldn’t have said it if she hadn’t meant it. I admit I felt great relief. I’d been discouraged at times wondering if my avocation was a fool’s errand. Professor Batorska was an authority figure to me, a student, and her simple validating comment meant more to me than a New York Times review.

Diane Dawson and Sylvia Selfridge of Cape Ann brought Theresa to Sugar Land the following year. Theresa approved of the house, and although by this time her mental acuity was fleeting, I think she remembered the visit. When Pastor Marty was saying grace at one of the dinner parties, Theresa, showing her old spirit, said, “I can’t hear a goddamn thing.”

Also in 1999 I set up Bernstein House Foundation with two paintings and profits from Joan Whalen’s February show. The stated purpose—required by the IRS—was to further understanding of Theresa’s art. Tish continued her research in Austin, Washington, Cape Ann and New York for a monograph to be funded by the foundation. Learning of the Bernstein House Foundation, Theresa was looking forward to Tish’s publication.

With several five-figure donations from collectors, some small donations and the sale of one of the foundation paintings, $100,000 plus was accumulated over the years. I’d paid Theresa a royalty on sales from works of hers I’d bought from her. After her death, her royalty went to the foundation before the foundation was dissolved in 2010.

When Theresa died, I rode to the cemetery on Long Island with a niece of William’s. She talked of family outings as a child when Theresa and William would accompany them. The car would be packed so Theresa sat on William’s lap. As they rode, Theresa would say “Oh William, oh William, OH WILLIAM.” What a dynamic personality. Giving time a run, hers was a life fulfilled. And partly thanks to her, I can say the same of mine. I’ll always be grateful I went to Joan Purcell’s barn in Bar Harbor in 1966. Theresa was mentor to many of us lesser mortals, to me as much by example as with her keen mind.

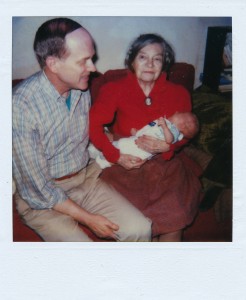

Theresa Bernstein and William Meyerowitz visiting Girard Jackson at him home on Rock Spring Rd., Stamford, CT in 1973: